| title: | Introducing VT, The Val Town CLI |

|---|---|

| description: | Introducing VT, the official command line tool to edit, manage, and begin Val Town projects from the comfort of your terminal! |

| pubDate: | 2025-04-17T00:00:00.000Z |

| author: | Wolf Mermelstein |

Introducing VT: the official command line tool to edit, manage, and begin Val Town projects from the comfort of your terminal!

Val Town gives you a super fast, intuitive, and powerful way to instantly create (and deploy) websites. But until now, this entire experience has been on the web. There's a lot of reasons to want to work on your Val Town projects locally. Maybe you want to work from the comfort of your favorite editor, whether that's vscode, with your favorite extensions, theme, and keybinds, or Neovim and tmux. Or you want to access powerful local devtools, like ripgrep or sed, or increasingly AI powered modern ones like Claude Code or AI powered IDEs like Cursor. Maybe you want to use git, or some other version control system outside of Val Town. Or maybe you want an easy way to port a non-Val-Town project to Val Town. Now you can!

vt is designed to be a simple, robust, interactive CLI to interface with val town projects.

With VT, you can:

vt clonea val town project to a folder, and thenvt watchthat folder, so that as you make changes locally they are automatically pushed to val town. This includes editing, creating, deleting, and renaming vals.vt checkout, and manage multiple branches locally, working on multiple features at once.vt createorvt remixto start new projects locally, andvt listandvt deleteto manage your Val Town projects.- And more!

vt is also fast! Operations all happen concurrently whenever possible. Watch 62 files get cloned in 0.17 seconds!

vt is still in beta, and we'd love your feedback! Join the Val Town Discord to leave feedback. Vt is built entirely within Val Town "userspace" (with the public API), and the codebase can be found at https://github.com/val-town/vt .

To get started using vt, make sure you have Deno installed, and then run

deno install -grAf jsr:@valtown/vt

To authenticate with val.town, just run vt, and you should get the dialog

Respond yes to the prompt, and ensure you select to create an API key with user read & project read+write permissions.

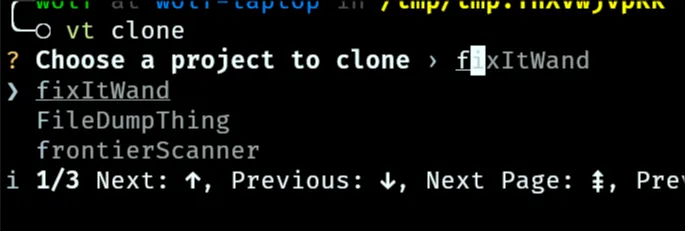

Then try cloning one of your projects with vt clone!

Which will open up a menu with all of your projects that you can clone. You can actually clone anyone's project, but you won't be able to push if it isn't yours (you can always vt remix though!).

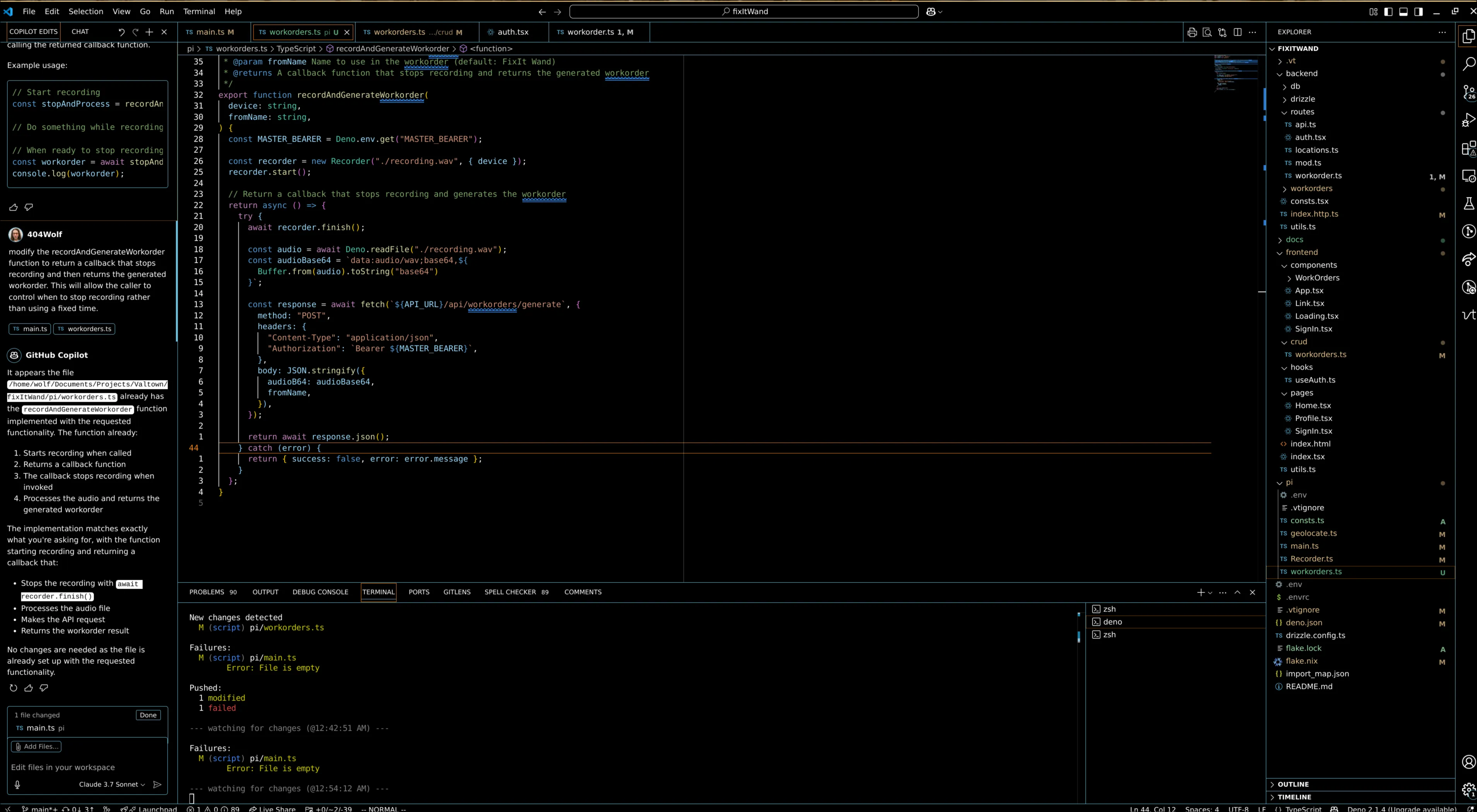

Once cloned, you can run vt watch to enable automatic syncing with Val Town. When you edit the project locally, it will automatically upload the changes to Val Town. You may find it useful to use a terminal window in your editor of choice so you can easily see the changes being pushed and see errors.

Finally, fire up your favorite editor and start creating!

For more information, head over to the vt JSR page!

For the curious, here's a technical overview of the making (and origin) of vt.

There's a lot of different ways we could engineer a local Val Town experience.

One of the very first sight of Val Town "localdev" came with Pomdtr's Val Town vscode extension. The extension was pretty straightforward, it hooked into the Val Town API to let you edit your vals locally and then push them to Val Town. It was made pre-project era, so it only supports traditional Vals. VSCode runs on electron, and gives extension developers a lot of power; the extension also offered web previews, and the ability to use Val Town SQL and blobstore.

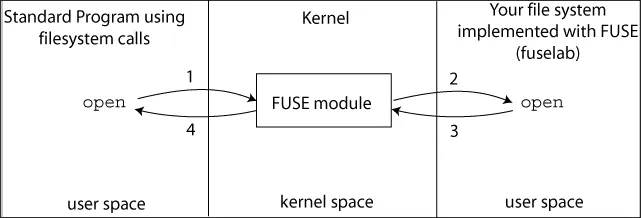

A bit later, I came along and implemented a fuse file system for Val Town vals, also pre-project era. Fuse is a Linux protocol that lets you implement arbitrary file systems in userspace. By implementing a fuse Val Town file system, all edits locally are instantly reflected on the Val Town website, and vice versa (if you update remotely, then if you try to save locally your editor will say something along the lines of "more recent edits found, are you sure you want to write"). Fuse is very powerful -- writes, reads, and all other file system syscalls can be handled with whatever response you want.

This project was vtfs. Originally it was a side project of mine, because "can I write the code in neovim" was the first question I asked myself when I first started using Val Town. I love the elegance of a file being a website, and thought it would be fun to be able to do a "touch website.ts" to create them, via the magic of fuse, and Val Town! There's a lot to love about the perfect 1:1 mapping of Val to File.

And so I built it! valfs was really cool: you'd run vt mount [dir] and you'd get a folder with all of your vals in it.

vtfs was built written in go with go-fuse, because, well, I didn't want to deal with C++ package management, and I wanted to try go. go is super cool, it's like a "cleaner" c with actually pleasant devx, and the best type of imports (URL imports!).

Fuse is a two-part system that involves userspace/kernel-space communication via a special "wire protocol". The official userspace "reference library" for implementing fuse filesystems is written in C, but what's cool about go-fuse is that it's entirely rewritten in pure go (not just a wrapper with cgo).

We decided to rewrite it mostly for compatibility reasons. Linux offers native fuse support, but MacOS and Windows definitely do not. For Mac, there's a project called MacFuse that acts as a kernel extension to provide fuse support to Mac. However, it's not totally stable, and Apple is deprecating kernel extensions and it may not be the best long term solution. There's a really cool project called fuse-t that takes a different approach, where it implements the fuse protocol by forwarding fuse to NFS (network file system), a protocol that Macs do naively support.

One idea we had to avoid dealing with fuse was to build a generic FTP server, largely inspired by Pomdtr's Webdav server. His server works totally in userspace and maps the Val Town API to Webdav really nicely. Webdav is a generic "file system" ish (it's quite limited) protocol over HTTP, and making a FTP server would just be implementing on a fancier file transfer protocol that's more capable. What's nice about using protocols like these is that you can then just use rclone for mounting or syncing.

In addition to compatibility issues, implementing a fuse backend is just plain complicated. The way valfs worked, on every write syscall, valfs would have to parse the file, extract metadata, and do multiple API calls. Even though vt is a total rewrite, many design choices for vt came from vtfs, like considerations on how we handle metadata, the notion that "a val is a file," and more.

At its core, vt was built to be a decentralized synchronization tool. Unlike vtfs, where the sync is guaranteed and live, syncing happens asynchronously with vt (even when "live syncing" with vt watch, which is only "psudo-live" since you could create conflicts by updating state on the website while watching). We rebuilt vt in typescript with Deno, because, well, we (and our community) love typescript and Deno, there's an official typescript sdk for Val Town, and because we have hopes of turning vt into a esm library in the future (so you can use vt in your own, non-val-town workflows).

We originally wanted to host vt itself on Val Town, where we would begin development with git and github, and then eventually transition to using vt itself to continue development of vt (bootstrapping!).

Early on, however, we ran into a lot of trouble with path aliases. When you use http imports for libraries (as you would if we hosted vt on Val Town, since you'd do deno install -grAf https://esm.town/std/vt or similar), all the imports need to be relative since you lose all the configuration of your deno.json. This is an issue with Deno that is "expected behavior". We did consider at one point just caving and making all the imports relative, but it really sucks to have imports like import foo from "../../../../../foo.ts"; all over the place. Unfortunately, this is a platform limitation that we still need to solve. One idea we had to get around this was to install the source code locally in a temp directory with the deno.json via a (http importable) install script. I even wrote a Val that generates the install script to make this work for any project!. You can see this in action (and it might still work!) by visiting https://run-with-deno-json.val.run/gh/val-town/vt/main/vt.ts (notice how you put the entrypoint to the http library in the url path). We used this approach for a bit, but eventually ran into weird issues where Deno would keep the old version cached even if you did a new install with -r, which we never totally solved but I imagine is related to the fact that the entrypoint of vt, vt.ts, itself never changed.

vt also has a lot of automated tests, and currently Val Town doesn't offer automated CI.

vt is heavily inspired by both git and gh, the github CLI. There's elements like vt push and pull that are very gitty, and things like vt create that act like gh repo create. Or, commands like vt browse, similar to gh browse, which opens up the current project in a web browser.

Like git, vt "Projects" are denoted by the existence of a dot folder -- in vt's case, .vt. This is also where state and configuration data lives for the project. Right now, the only thing that lives in .vt is state.json, which contains information about the current version of the project checked out, and the project and branch id.

Unlike git, where you have a stage and commits, vt only has a notion of pushing and pulling. This means that the local state could conflict in ways with the remote state that could result in changes that we can't reconsile: like, if you pull and you have newer changes locally, or If you push and there are newer changes in the remote.

We spent a while considering what pushing and pulling meant. The conclusion we came to:

pushingis a forceful procedure. When you push we ensure that the remote state matches the local state, and by the end of the push the remote state should match the local state with no changes to the local state. This might sound scary, but we do versioning for projects, so in the worst case you could revert to an earlier version on the website and pull.pullingis a "graceful" procedure. When you pull, you may receive modifications, deletions, creations, or renames to local files. For all of these changes except creations, pulling warns the user that local changes will be lost, and you need to confirm to complete the pull. This is implemented internally by doing a "dry" pull and checking what changes would be made locally.

This means that the contract for push is "push the local state to make sure the remote matches it" and pull is "get the remote state and make sure the local state matches it."

One totally different idea that I had to solve this problem of "the meaning of push and pull" was to totally scrap both, and change the contract to "sync to a consistent state." As it turns out, syncing really just redirects all the complexity, and is still quite complicated to implement.

I spent a while designing an algorithm for syncing, where the primary "building block" of the algorithm was to "walk" through revisions and make changes to the local state incrementally. Because of how Val Town does versioning, the changes could be applied one version at a time.

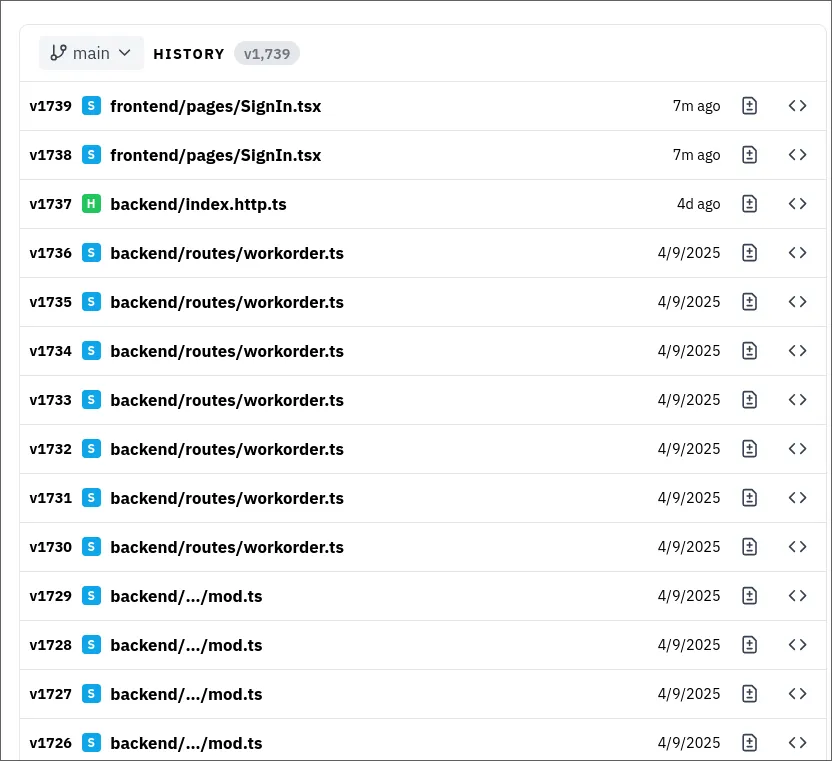

On the subject of versioning: the way Val Town does it made developing vt easier since versions are just increasing integers, but as a user numbers are sort of meaningless. In one project I'm working on, I've hit versions in the thousands! My solution to make versions more useful is to maintain a versions.txt file that adds messages to specific versions. Right now, reverting to an older version is the same as doing a force push to the current branch with that version, and this can be done via the web ui (and is not currently a vt feature).

Syncing would start by pulling to incorporate all remote changes locally, and then push the remainder. It also would look at modification times to try to guess which update should be kept in the case of local/remote conflicts. Here's the actual proposed algorithm for the curious.

With the way vt does git, we get a lot of internal logic "for free." Many of the internal vt operations are able to easily piggyback off of one another in (sometimes) mind bending ways. Like vt push --dry-run being the same as vt status, vt pull just does a vt clone, and then removes stuff that does not exist on the remote that still exists locally, or vt checkout is somewhat like vt pull-ing the branch you are trying to check out. These abstractions make testing and maintenance much easier.

There's been some discussion of how far we should lean into the git analogy. For example, vt has command flags like checkout -D/-b, where, without the existence of git would probably be branch create branch switch. We don't think there's a "correct" answer here, and are open to thoughts on what would be most intuitive/ergonomic for folks. Even git can't always seem to figure it out.

We also considered and even implemented at one point adding support for vt stash, so you could save local changes that you didn't want to push, but decided that we wanted to keep Val Town as the source of truth and try to avoid adding additional states. We may return to this later, since it would be nice to be able to "scrap" local changes without totally losing them, though. One thought is putting these changes into a "scratchpad" branch instead of storing them locally.

Finally, something we knew early on is that people would need a way to opt out of syncing stuff. Originally, I thought this would be really straightforward, just add a .vtignore, and implement it like a .gitignore: a newline separated list of globs. But it turns out that .gitignores are kinda complicated, and it isn't quite like that. I started down the path of trying to implement this myself, but eventually decided to use a gitignore-parser library that I found. There's really interesting fancy gitingore behavior you've probably never thought about, like if you have conflicting patterns like !foo.tsx and foo.tsx, later ones take president, and / prefixed stuff is relative to the root of the git directory. Git has a whole man page on it!. We still don't have perfect parity, like .vtignores apply for the entire project and not just "lower" files like they do in git.

One other question with ignore files that is ongoing is whether we should name ours .vtignore (in the style of .npmignore, .dockerignore, etc), or, like some tools like nix, just re-use .gitignore. We are still considering what to name ours, but right now use .vtignore.

One of the most important use cases of vt is "watch" functionality. There's a lot of reasons for this. One of the big ones is that, as you (and maybe your favorite LLM) edit your code locally, it is really handy to remove the friction of syncing with Val Town.

From the beginning, my plan for this was to implement "git" behavior first (pushing and pulling), and then just doing file system watching to add live syncing using Deno.watchFs to handle file system events.

One particularly annoying challenge with vt watch was handling debouncing. Deno's standard library has an async module that was super useful for implementing vt watch. vt watch works by doing a push initially, and then whenever local changes are made running another vt push. It sounds super simple, and it mostly is!

The issue is that there's a lot of different things that could trigger a "files were changed" notification, and doing the push itself is one of them (which took a painful amount of time to figure out: the .vt folder has files internally that get updated on a push, like book-keeping ticking the version). Instead of working out the corner cases, I added a grace for post-pushing before we are able to detect file changes again.

I also debounce the push. Initially, I did this so that if you are doing large amounts of file modifications we wait until you're done before starting the push, but it turns out this is more important because of how editors will create ephemeral temporary files during writes. Now, when you edit a file, the editor might create transient files, but as long as it gets rid of them within the debounce the final state that gets pushed is the one that does not include those temporary files.

Another aspect of this live dev experience is the friction of having to reload the website as you make updates to the website. Unfortunately, even though we can and do open browser tabs, browsers' CLIs do not expose a way to redirect or reload open tabs unless you launch the browser with remote debugging (think puppeteer).

One idea I have for solving this problem, which I think will be the best long term solution, is a minimal browser extension that uses a websocket to talk to vt, and have vt watch use Deno.serve to host a minimal websocket server on localhost that pushes when the project gets updated. Extensions can reload tabs, so this would give vt the power to tell your browser to reload tabs. This is still just an idea, and will be tested soon.

Steve has been working on a more general solution to this problem by injecting code into the website that detects updates and reloads using a Val with long polling. There's a demo of that here, the general idea is that it polls the latest version of the project and reloads the page on updates. This works outside of vt too.

Internally, vt is broken up into two main parts: the vt lib, where the actual logic for push, pull, and other "git" operations is defined, and the vt cmd lib, where the CLI logic is laid out. Eventually, we want to make vt a esm library, where we expose the functionality of the vt lib component.

For both cases, we're using Deno's native testing framework. For vt lib, it's pretty straightforward, where we run tests in temp directories doing things like pulls or pushes, and then use the sdk to verify changes.

For the command library, the CLI framework we're using for vt (cliffy) has a handy Snapshot test module that vt doesn't use. We decided against using snapshot tests mostly because we lose a lot of fine grain control. Instead, we took inspiration from cliffy in running the CLI tests as subprocesses, and make a lot of use of Deno's assertStringIncludes on stdout. One ongoing issue we've had with testing is that we've encountered a lot of "resource leaks." It's really cool that Deno tests can detect unawaited promises or unawaited/cancelled request bodies, but it doesn't do a good job of helping us locate where the issues are.

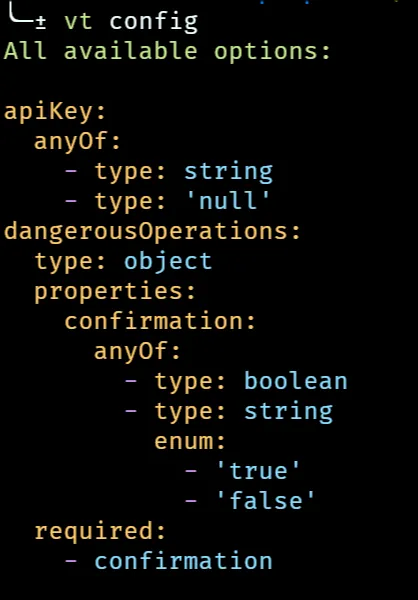

vt stores configuration in <your system configuration directory>/vt/config.yaml, and loads it using zod. There's some interesting mechanics where we have multiple layers of configuration, like local and global, and prioritize configuration options in order. Once again, Deno's standard library has been really handy in building out these components, like the deepMerge function.

To figure out where your system configuration directory is, usually I'd use npm's xdg-portable, which gets us your os-aware configuration directory, but it turns out that using this via npm:xdg-portable doesn't work with Deno, and we can't use the officially recommended http import version since jsr, the registry we publish vt to, doesn't support http imports. I looked into this, and it seemed like an issue with their build process not including their Deno code. The solution I decided on? Fork xdg-portable to be Deno native! In the process, I removed a ton of bloat.

There's also a lot of fun interactive niceities that the CLI provides. Right now, vt is primarily designed for the human user, but we plan on adding better scripting support down the line.

vt takes some inspiration from Pomdtr's previous vt CLI, which served more as a management tool. Like his tool, vt uses the Cliffy CLI framework, which, although very new and not super well established, has served every use case we've come upon for vt. It's interactive capabilities and tty module have been super helpful to crafting some of the fancy interactive elements of vt.

tty.cursorSave // Monad-ic tty manipulation is so cool!

.cursorHide

.cursorTo(0, 0)

.eraseScreen();

I'm also using highlight.js, right now just for configuration commands, but in the future may also use it if we add vt diff.

One of the initial concerns was how one could edit val metadata locally, if we are limited to the context of files.

vtfs's approach to this was to pack all of the metadata for a val into the file corresponding to it. For Val Town projects, it's a bit more complex, because there's metadata specific to vals in the project, and metadata for the entire project itself too. We decided that, in general, changing val metadata and other uniquely val town attributes is something that we would leave to the website.

vtfs would indicate the type of a given val locally as foobar.H.tsx (or, if verbose, foobar.http.tsx), which was a really nice pattern. If you wanted to change the type of a val, you could just rename it to foobar.script.tsx. This pattern, however, turns out not to work as well for projects because vals in projects generally are suffixed with .tsx, so you would end up with foobar.http.tsx.tsx, and it would get messy quickly -- and there were some issues with Vscode not liking .script.tsx. In general, it's a bit scary to introduce magic like this.

Instead of doing strict enforcement -- maintaining a 1:1 mapping of file extension to val type -- vt intuits the val type only on creation. If you create a foobar.tsx, vt sees .tsx and assumes it's a script. If you create foobar_http.tsx or foobar.http.tsx, vt sees .tsx, knows it's a val and not a file, and then guesses it's an http val. But it never will change it after the fact, so you can change foobar.http.tsx to be a script val on the website, and that's what it will continue to be going forward.

It might seem simple at first, but if you think about it, detecting whether a file was renamed is actually really tricky. If we move foo.ts to bar.ts how do we know that it wasn't a CREATE bar.ts and DELETE foo.ts? Originally we didn't plan on adding rename detection support to vt because of all the complexity that comes with rename detection.

But then we realized that, without rename detection, if you move a val with configuration -- like cron config, or custom endpoint HTTP vals, then doing the deletion/creation would cause you to lose all your config! And so, we added rename detection to vt.

The rename detection algorithm is a bit complicated -- it works by looking at all files that got deleted and that got created, and then considering a file as renamed if a created file is sufficiently similar to a file that got deleted. When iterating over created files to see if a deleted file is similar enough to one of them, we use some heuristics to filter out files that could not possibly be similar enough, like the file length. Then we compute the Levenshtein distance between a given deleted file and created file, and consider a given created file "renamed" if it is above some theshold similar to a deleted file, and if it is similar enough to multiple, then the one it is most similar to as it turns out, Deno's standard library has a super efficient edit distance function. Git does fancy directory rename detection, which is something that, at least for now, vt does not do.

Because rename detection is relatively expensive, it is internally implemented as an optional operation that doesn't always get used for every vt operation. For example, there isn't a lot of reason to do rename detection for vt pull -- it would really just be for reporting.

There's some fun features of vtfs that didn't end up making their way to vt, like blob support.

For vtfs, a core feature was going to be the ability to "mount" your val town blob store so that you could view, edit, and organize your blobs locally. With fuse, there's a ton of flexibility on how to "implement" inodes. go-fuse provides a lot of nice abstractions. For totally static files like deno.json I was using the MemRegularFile helper, which makes it trivial to create an Inode with static text contents. For Vals, I was doing it more manually, implementing the read and write methods for a custom ValFile Inode myself. But for blobs, I wanted to handle reads and writes by streaming the relevant portions of the file.

When implementing my own write callback for fuse, I would be handling requests to write data to a region of a file (like, write 0001010101 starting at index 22 bytes). Our /v1/blob endpoint is somewhat restrictive here. You can only write an entire file, or get an entire file. vtfs would show you all your blobs by using the blob list endpoint when serving "list directory" syscalls, and when you tried to access a specific blob would download the blob to a temp file and internally manage the bookkeeping to map read calls to that temp file (read 1-11 from fooBlob == read 1-11 from /tmp/f90jjf2j-fooblob).

Handling writes was particularly tricky -- I could start a new upload to upload the entire state of the file, with the new change made in the current write call, but if you're writing a lot of data to a file (like if you cp bigFile.png to the folder that I was using to represent your val town blobs), then there would typically be a burst of write requests to write to consecutive regions of the file.

I spent a long time working on setting up a pipe where I would handle consecutive writes, writes that start at index i, end at index i+k, and then a new write that starts at index i+k+1, etc, as a special case. Eventually, I got something working!

For vtfs I was using Openapi Generator, and it turned out that Val Town's OpenAPI specification didn't accept file sizes on the order of my tests -- where the response would include the file size, it was an integer, not a format: int64 (long).

Maintaining this, and getting writes to work non consecutively continued to prove a huge challenge. valfs blob read/write support was a fun challenge to work on, but was never totally reliable.

vtfs also had tighter Deno integration, which is something that we're still deciding if we want for vt. For example, with vtfs, when you mounted a folder, vtfs would automatically run deno cache /path/to/thatDir for you, to make sure that your language server would always have the types for all of the libraries that you were using. Additionally, we have a default deno.json file that is taken from vtfs, which includes the Val Town type declarations like the Email interface, that only show up after you run a deno cache from that directory.